The fishing sector around the world faces many challenges, including pollution, over-fishing and climate change. Regulation and management of the fishing sector is essential to ensure that stocks are sustained and that operators behave responsibly. But enforcement of those regulations requires transparency and accountability. Only when you know who is accountable for the fishing fleet can you enforce standards.

A recent report by the Environmental Justice Foundation considers illegal fishing, including in Ghanaian waters. It alleges breaches of Ghanaian law by fishing boats ultimately owned by Chinese operators. The impact of illegal fishing is felt by the legitimate fishing industry in the country, and in the case of Ghana this has impacted on the local fishing fleet who rely on the fishing sector for their livelihood.

In order to tackle illegal fishing, coastal states need to know who is accountable. Fishing is prone to undisclosed foreign ownership, where local activities or fishing fleets are ultimately owned or controlled why unknown foreign parties, through complex corporate structures. In addition, many of the boats making up the fishing fleet might be registered under flags of convenience.

Another key issue is control. There are lots of reasons why governments want to understand who controls how much of the fishing sector. These could include issues of security of supply and the risk of the concentration of power in the sector in the hands of a small number of dominant individuals. The use of anonymous shell companies and complex corporate structures can make it impossible for governments to really understand the landscape of power within the sector.

Beneficial Ownership (BO) is the concept of identifying the natural persons who directly or indirectly own or control companies, looking through any complex ownership structures or shell companies. This can be an effective tool to help tackle money laundering, corruption and other financial crime, and many countries around the world are implementing BO regimes of their own, applicable to companies registered in their country.

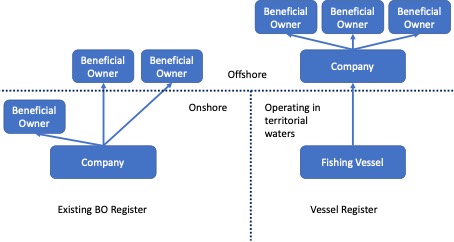

In many cases these BO regimes are economy wide, and apply to companies in every sector of the economy, and even the local branches of overseas companies. Ghana is an example of such a country. Ghana has over the last 2 years introduced a BO regime and is collecting BO data in a public central register.

So are these beneficial ownership registers the answer to improving governance in the fishing sector? Well, perhaps. But sadly it isn’t as simple as that.

When a country introduces a BO register, that captures information about the BO of companies registered in that country. But what about foreign registered fishing vessels? Well, unless that are owned through a local company, the BO register doesn’t really help.

So what is the answer?

Vessels carrying out illegal fishing are owned somewhere, and in most cases will be owned by a company. So one solution would be to consult that BO register of that country. But this option has 3 main flaws:

- You would need to know where to look. You would need to establish which company owns the vessel, and where that company was registered. Only at that point could you consult the appropriate register.

- There are still very few publicly accessible BO registers in the world, and in particular, China does not have a public BO register. There may come a time when there is a network in interconnected public BO registers around the world, but this is a long way off.

- Searching for the BO of a vessel which has committed an offence will always by definition be after that fact, and less effective at preventing crime.

There is another solution, which is to build BO transparency into the licencing process. Requiring vessels licenced to operate in national waters to provide verified BO information will allow law enforcement to take proactive action as soon as unlicenced vessels are identified in fishing waters.

There is a parallel here to work ongoing in the UK to introduce a register of the beneficial ownership of real estate owned offshore.

However, the challenge should not be underestimated. As with any BO register, verification of the data is vital. A determined criminal will make every effort to disguise their interests, and a vessel register would need to have just as many verification measure and sanctions as a company BO register. This is an essential aspect of the design phase, which is stage six of our beneficial ownership implementation framework, BO6.

BO started as being just about knowing who owns or controls companies, but as the use cases for this information become clearer, it is evident that transparency in ownership is key to governance and enforcement in many other areas.

Governments who have already implemented a BO register for companies, or who are currently in the design or implementation phase, should consider whether there are other BO tools, such as a register of the BO of licenced fishing vessels, which would assist in tackling criminal activity.

Michael Barron and Tim Law are independent consultants that have advised governments on four continents on implementing effective beneficial ownership reporting systems.